|

Defiant T3955 - Nether Kellet

15th May 1941 |

Last

updated: 05.12.2017

|

256 Squadron Defiant I

|

|

| Type |

Serial |

Unit |

Base |

Duty | Crew |

| Defiant I |

T3955 |

No. 256 Squadron |

Squires Gate |

Night practice flight | 2 |

The

aircraft involved was an RAF Boulton Paul Defiant I, Construction

number 495, built under contract 34864/39 and delivered to No. 19 M.U.

(maintenance Unit) on 5th March 1941 with the RAF Serial No. T3955. On

the 10th April it was allocated to No. 256 Squadron, based at Squires

Gate near Blackpool and given the Squadron code letters JT-R. The

Defiant was a pre-war designed Interceptor aircraft intended to attack

enemy bomber formations and was armed with a powered dorsal turret,

equipped with four 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns, requiring a

gunner in addition to the pilot. At the time of its loss, Defiant T3955

had only completed 39 flying hours. On the night of the 14th / 15th May

1941, T3955 was being flown by Sergeant P.J. Taylor accompanied by his

air gunner, Sergeant E.R. Fremlin RNZAF on a night practice flight. The

aircraft crashed 01:45 hours on the 15th - the cause being officially

recorded as "after losing control due to inexperience in instrument

flying in poor visibility at night". The aircraft dived vertically into

the ground and was totally destroyed by the impact and ensuing fire,

with both crew being killed instantly.

|  |

| Sergeant P.J. Taylor | Sergeant E.R. Fremlin |

| Name | Age | Position | Fate |

| Sgt. Peter John Taylor | 20 | Pilot | K. |

| Sgt. Erle Rutherford Fremlin RNZAF | 19 | Air Gunner | K. |

Our

initial research centred on the crash record card (Form 1180), as no

AIB report could be traced. Immediately we noted that the date on this

form may easily be misread as "15.02.41", which explains why other

sources have mis-quoted the month for this incident in the past.

Blame for the crash is attributed to “bad instrument flying” by the

pilot and his O.T.U. (Operational Training Unit) assessment is

questioned as to whether it justified sending him to a night fighting

squadron. However other factors are mentioned, including the

deteriorating weather conditions on the night of the crash and the fact

that Link Trainer facilities were not yet available to the Squadron,

which no doubt contributed towards the pilot’s lack of further training

on instrument flying. Finally the possibility of an unknown mechanical

failure being a contributory factor is not ruled out. This latter

comment is interesting as one member of our group corresponded with

Taylor’s commanding officer at No. 256 Squadron several years ago and

he stated that a number of the Squadron’s Defiants had suffered major

instrument malfunctions around this time. This later proved to be due

to an identified common fault where the flexible rubber tube connecting

the engine driven vacuum pump to the artificial horizon and giro

compass was incorrectly fitted and became kinked cutting off the vacuum

supply.

The aircraft and engine were both categorised as “W”

or "write off" with fire noted on impact and although the Form 1180

indicates that parachutes were used, this again appears to be an error,

as both crew were clearly still in the aircraft on impact and were

killed instantly - though again other sources have mistakenly recorded,

in the past, that both crew bailed out and assumed they were killed due

to being too low. The Squadron’s ORB (Operations Record Book Daily

Summaries (RAF Form 540) held at the National Archives) states on May

15th that the aircraft dived vertically [into the ground] and burst

into flames. A few days later another entry on the 19th notes

that both crew member’s remains had been recovered from the crash site

and were transferred by road to the pilot’s father’s home pending

burial. It is believed personnel from the Royal Engineers carried out

the recovery and both men are buried at Mansfield (Nottingham Road)

Cemetery, Graves; 2603 (Fremlin) and 2402 (Taylor).

|

| Our initial

survey of the crash site in far from ideal weather conditions! |

We

knew that following the crash there had been a concerted recovery

operation to locate the remains of the crew for burial and believed

that the bulk of the aircraft’s remains were also removed at this time.

Also we knew that the site had been excavated in 1983 and parts

recovered at that time included; the instrument panel, a machine gun

and parts from the engine – with some items now being on display at the

Tettenhall Transport Heritage Centre in Wolverhampton. The

approximate location of the crash site proved to be common local

knowledge, no doubt largely due to the previous excavation, but the

original crash was beyond the memory of any locals we were able to

trace. Initial grid searching using conventional metal detectors was

used to ascertain a more accurate area of impact, through plotting the

characteristic scatter of smaller surface fragments and during this,

only a few of the more substantial, contacts were actually uncovered to

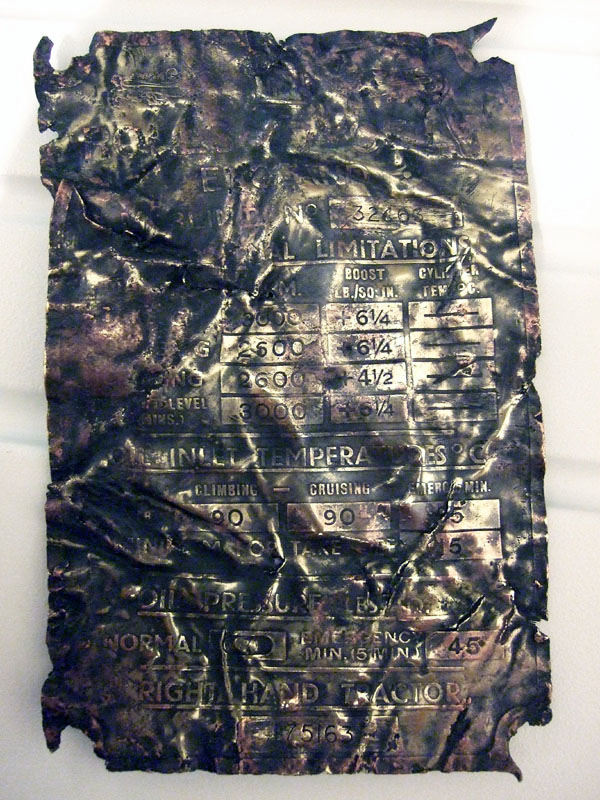

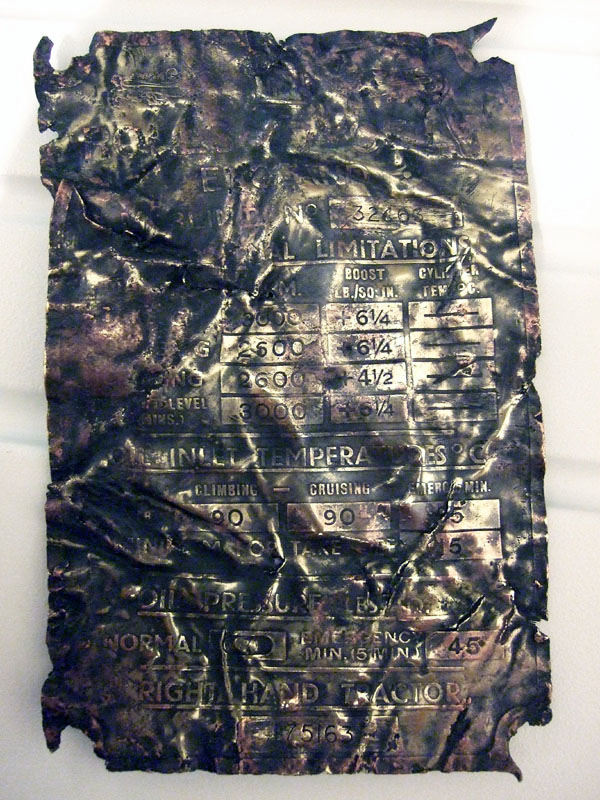

confirm their identity. These included, the maker’s plate from the

Rolls Royce Merlin engine, bearing the engine number, which matched the

documentary records. Also two instrument faces, one being the cockpit

clock, though both badly corroded. After marking out the apparent

limits of the crash site, more sophisticated detecting equipment was

used, including a Foerster Magnetometer, to search for deeper and more

substantial remains and although a few deeper contacts were noted,

there was no indication that these were likely to be major

remains.

|  |  |

| Before: Crumpled engine maker's plate, as found | After: Rolls Royce engine maker's plate cleaned and straightened | Face from the cockpit clock, with traces of the hour hand still pointing towards "1" |

For

our excavation of the site, we started by clearing the topsoil,

revealing an easily identifiable area of disturbed ground (see photos)

and almost immediately made our first find - a lead mass balance

weight probably from the rudder. This was right at the limit of the

excavation and was probably the only artefact we found in its original

undisturbed post crash location and strongly suggested a vertical

impact. The soil removed during the excavation had clearly been

heavily disturbed and there was no evidence of any discolouration

indicating burning or where parts of the aircraft had passed through.

Also noted was a layer containing substantial pockets of almost

completely oxidized powdered aluminium (Daz) at approx 3 – 4 feet

in depth, which we believed to be all that was left of parts of the

aircraft returned to the hole after the previous dig. This appeared to

be confirmed later when a visitor to the excavation proved to be the

driver of the machine used in the 1983 dig, who recalled the group

throwing quantities of airframe parts back into the whole at a point

when it was mostly filled in.

|  |

| Initial clearing of top soil revealing tell-tale traces of "Daz". | Next layer reveals discolouration of the sub-soil |

At

approx. 5 feet in depth a small scattered cache of parts from the

aircraft was found, with a few sections of steel framework and smaller

components, all showing significant corrosion, but better preserved

than the badly oxidized parts found so far. After removing these the

excavation was checked with our detecting equipment again and it

appeared that more still remained buried. At around 7 to 8 feet below

the surface the digger uncovered several medium sized boulders,

followed by a particularly large and immovable boulder at approximately

9 feet. This appeared to have suffered impact damage, probably

explaining the severe disintegration noted on the engine components

uncovered in 1983. The soil at this depth was darkly discoloured with a

faint smell of oil and fuel and it was found that although we were

still getting metal detector readings, no significant metal objects

could be found, only a few small pieces which proved almost impossible

to pinpoint with detectors due to the heavily metal fragment / particle

contaminated clay.

|

|

| Approx 5 feet in depth discolouration becomes more prominent | Parts recovered from approx 5 feet depth, including 2 oak blocks |

Overall the parts found showed no relationship to each other

in the order and location they were found, but there were clues that

suggested that the 1941 recovery had been very thorough and

probably reached the limit of penetration of the aircraft. Two oak

blocks found had almost certainly been used as sheerleg pads in 1941

and there was evidence of a fairly severe post-crash fire, probably

burning underground, as fragments of shoes were found (but reinterred)

that were charred and globules of once melted aluminium were found.

Most of the parts found exhibited severe impact damage, with a 12”

section of camshaft with a section of rocker cover wrapped almost

completely around it, graphically illustrating the extreme destruction

of the engine. The Rolls Royce maker’s plate from the engine was found

on the surface and was thought likely to have been brought from deeper

down by the 1983 excavation and missed in the spoil. This was also

badly distorted and crushed and took several hours work to unfold and

conserve. Also found on the surface were two instrument faces

from the cockpit which due to their fragility could not have survived

in this position since the crash, so again were probably missed by the

1983 team. Though badly damaged and corroded, the clock face did have

the remains of the collar and stub of the hour hand still attached,

pointing towards the numeral 1, appearing to confirm approximately the

time of the crash given as 01:45 on the crash record card.

|  |

| Careful checking of the spoil proved difficult due to considerable metal particle contamination of the soil | Site carefully reinstated at the end of the dig |

Acknowledgements:

Mr C Halhead, Russell Brown,

RAF Form 1180: Defiant T3955, 15.05.1941

256

Squadron’s ORB (Operations Record Book Daily Summaries (RAF Form 540)

held at the National Archives) entries for 15.05.1941 and 19.05.1941

Squadron

Leader E. C. Deanesly, D.F.C. (Deceased - former commanding officer of

256 Squadron), written correspondence circa 1987.

Mrs Dorothy Julia Taylor-Eggleshaw, (Deceased, sister of Sergeant P.J. Taylor), written correspondence circa 1988.

Mrs Melva Ockleston (Deceased, sister of Sergeant E.R. Fremlin), written correspondence circa 1988

Mr Peter. Taylor-Lane (Nephew of of Sergeant P.J. Taylor), email correspondence circa 2009

This page & all articles on this site

Copyright © Nick Wotherspoon 2017