|

Mustang IV KH 838 - Wrightington, Wigan 15th February 1945 |

|

Mustang IV KH 838 - Wrightington, Wigan 15th February 1945 |

Last updated 17.02.2011

This excavation project was the culmination of some 8 years research and negotiation with two consecutive landowners! It was filmed by the BBC for their Inside Out (North West) programme, which was aired on 14th February 2011.

|

|

| An RAF Mustang IV (P-51 K) - Note the slimmer Aeroproducts prop blades. |

Type |

Serial |

Unit | Base | Duty | Crew | Passengers |

| Mustang IV (P-51K) | KH 838 | A.T.A. | Kirkbride | Ferry Flight | 1 | - |

The aircraft involved in this incident was an RAF Mustang IV (US designation P-51K), Serial No. KH838, a lend-lease aircraft that had been transported to the UK by ship and re-assembled by Lockheed Aircraft Services at their Renfrew factory, near Glasgow in the West Central Lowlands of Scotland. The P-51K variant was in reality a wartime expedient due to supply problems with the Hamilton Standard propeller fitted to the P-51D Mustang and to keep production running an alternative hollow-bladed Aeroproducts propeller was fitted. Following reassembly, it was test flown on the 13th February 1945 and on the 15th February it was being flown from Kirkbride in Cumbria to Ringway near Manchester by an A.T.A. (Air Transport Auxiliary) pilot; Third Officer Albert Edward (Roy) Fairman, who had taken off at approx. 15.20 hours for this routine ferry flight. However, on arrival at Ringway, the pilot found the airfield fog-bound and had no option but to turn back. Shortly after, at approx. 16.05 the aircraft was seen by witnesses at Wrightington, apparently in trouble, circling the village and then performing a series of shallow dives and rolls at around 1000 feet. During a final roll the pilot was seen to leave the aircraft, which immediately dived into the ground under power, impacting at approx. 16.10 into a small holding, just off Church Lane, with the fuel tanks exploding and scattering burning wreckage across the lane, blocking the road. When found nearby, Third Officer Fairman was still alive, but died in the ambulance on the way to hospital - he had attempted to use his parachute, but it had been faulty, though he was probably too low for it to have deployed effectively in any case.

|

|

|

The house today. Note: the exposed brick wall is part of the original dwelling and the shrubs in the left foreground mark the crash site - showing how close the impact actually was. |

The rockery feature that has covered the crash site for the last 60 years. |

The Mustang had, in fact, impacted into a small pond in the front "garden" of the small holding, only a few yards from the house, apparently just as the Bannister family, who occupied the house at the time, were sitting down to a meal. Although the house was badly damaged, with the windows blown in and the roof partially ripped off, mercifully it did not catch fire and all the family members, who had thrown themselves to the floor believing a bomb had gone off, were apparently unhurt, though badly shocked.

| Position | Rank | Name | Service No | Age | Status |

| Pilot | Third Officer | Albert Edward (Roy) Fairman | 146431 | 23 | Killed |

Albert Edward (Roy) Fairman was

born and raised in Greenwich, he attended Sir Walter St.John's School,

Battersea, where he earned distinction in many branches of sport and before the

war he worked in the City office of a firm of Dutch bankers. He joined the RAF

right at the start of the war in September 1939, aged only 18 and at 19 years

old was apparently piloting bombers on raids over occupied territory - he

accumulated over 500 hours on operational sorties mainly flying Whitleys and

later Lancasters, being promoted firstly to Pilot Officer and then to Flying

Officer, until a severe flak wound to his leg required major surgery, which

included the insertion of a metal plate to hold his foot together. This meant he

was declared no longer fit for operational flying and he was seconded to the

ATA, though he was only permitted to fly single engined aircraft, where he

accumulated another 120 hours on ferry flights. On the morning of the crash he

was observed limping and it was noted that he felt effects of the wound in

damp and cold weather, which were certainly the prevailing conditions on what

proved to be his last flight. He is buried at Greenwich Cemetery, Greenwich,

Grave No. 972.

|

|

|

F/O Albert Edward (Roy) Fairman |

|

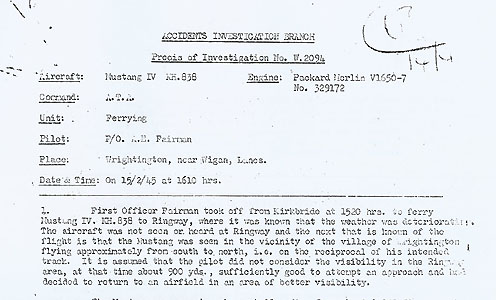

Due to wartime conditions only a small percentage of RAF crashes were

subject to full AIB (Accidents Investigation Branch) reports and of those an

even smaller percentage of reports appear to have survived to be available to

researchers today - However in the case of Mustang KH838, we are fortunate to

trace such a report, some 12 pages long and going into considerable detail.

However it soon becomes obvious that the incident was treated as a classic

"open & shut case" of pilot error – all too common a scenario,

in the experience of today’s researchers. Though we have to remember that

limited resources and a heavy workload, with so many fatalities occurring at

that time, meant that such conclusions often proved a useful expedient to

investigating teams in a hurry to get the job done and move on to the next one.

|

|

|

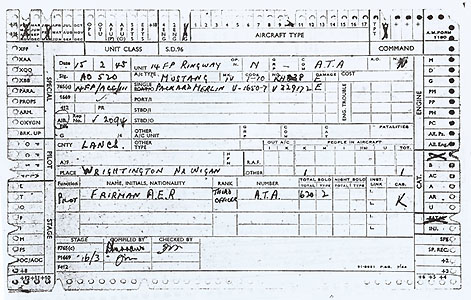

RAF Form1180 Accident Record Card - This is the main source of information for most incidents. |

Accidents Investigation Branch report into the loss of Mustang IV KH838 |

In fact many questions about the

cause of the accident remain unanswered, as it soon becomes obvious that

relatively little of the wreckage was recovered or examined. For example, it

states that the aircraft's engine was not recovered and therefore was not

examined – due to eyewitness stating that it was heard to be running up to the

point of impact! Also no readings were recorded from the aircraft's instruments

or the settings of the controls as they were said to be “totally destroyed”.

But perhaps most importantly, unusual head and eye injuries were noted when

examining the pilot’s body, which were attributed as evidence of the effects

of negative G or a severe blow to the head and therefore as a result of the

“aerobatics” and sudden ejection from the aircraft. Almost as an

afterthought the report then goes on to mention that the injuries could also be

evidence of even carbon monoxide poisoning, but states that no further tests

were carried out. This being despite it being known by this time that this type

of aircraft was prone to problems with carbon monoxide and fumes entering the

cockpit!

Other discrepancies in the

report begin to emerge as you delve deeper; The pilot is reported to have been

flying with the canopy open – at best very uncomfortable, but also potentially

very dangerous according to veteran Mustang pilots and current warbird pilots we

have spoken to – with trying to carry out aerobatics being considered an

impossibility. The overall consensus being that you would not open the canopy of

a Mustang in flight without a very good reason – especially over England at

that time of year and in those weather conditions! All the witnesses we

interviewed spoke of the plane circling the village several times before going

into a dive and crashing – yet no such flight pattern is mentioned in the

report – yet it would be the classic behaviour of a pilot who was lost or

having some sort of problem with the aircraft. Also even the reported manoeuvres

also do not fit into any recognised pattern of aerobatics, in fact they have

been identified by experienced pilots as being far more consistent with an

incapacitated pilot unable to maintain control of an aircraft or perhaps trying

to hold the aircraft steady with one hand whilst trying to open the canopy to

bail out?

|

|

| Tell-tale dark area to the centre of the excavation indicates where the aircraft's engine has penetrated the subsoil | Piece of steel armour plate with preserved painted finish and stencilled makers inscription still clearly legible after 65 years underground |

Today the crash site lies under

the front garden of a large up-market property that stands on the site of

the original small-holding's dwelling. However the original house was not

demolished, but has been extended several times and still includes rooms that

formed part of the original bungalow. The pond was never repaired, but was

filled in - probably with rubble

and rubbish from the extensive repairs required to the original dwelling after

the crash and was eventually replaced by a rockery feature. A magnetometer

survey indicated that the substantial remains of the aircraft still lay buried

and a small test pit revealed several small fragments of aircraft structure and

also signs of brick, slate and broken window glass together with broken pieces

of bottles of 1940s vintage.

|

|

| Unique to the P-51K model of Mustang, a distinctive Aeroproducts propeller blade is uncovered and removed by hand to avoid damage. |

One of the most important tasks on an aircraft dig - sifting through the mud and spoil by hand to ensure no small parts are missed. |

The excavation of this site took much careful planning and preparation and was eventually carried out over the weekend of the 26 / 27th June 2010. Although we always pride ourselves on our reinstatement of sites after our excavations, clearly this one required a lot of extra care and our thanks go to the digger driver, whose skill avoided creating much potential extra work. After the initial removal of the decorative rocks and shrubs, the first finds from the crater infill were many broken and several intact bottles dating from the 1940s. These proved interesting in their own right and of course proved that the site had remained untouched since shortly after the crash. Below this the first fragments of aircraft structure began to appear, many clearly affected by an intense fire and a distinctive darkly stained area in the clay and subsoil indicated where the aircraft had passed through. As this material was removed, larger fragments from the aircraft began to emerge, with each being in better condition than the last and soon a mass of tangled wreckage was uncovered, which required removal by hand to avoid damage from the digger’s toothed bucket. This precaution soon proved appropriate as a complete propeller blade was recovered, along with numerous smaller parts that were bagged up for proper examination and cleaning later. Larger more easily recognisable parts included the hydraulic accumulator reservoir, part of the armour plate from the bulkhead – still with the stencilled specifications and address of its manufacturer visible, broken sections of engine bearers and the shattered remains of the carburettor and supercharger. Below this material, various gearwheels and machinery could be made out – all firmly attached to something very solid and careful clearing by hand revealed the supercharger gearing and part of the cylinder heads, indicating we were looking at the back of a possibly intact Merlin engine embedded in an almost vertical attitude into the ground. After an hour or so careful excavating around the engine, it was finally time to prise it free of the hard clay subsoil’s grip and as it gently rolled to a horizontal position it became apparent that it was indeed as intact as we had hoped.

|

|

|

Arrows indicate the backs of the Cylinder heads of the V-12 Merlin engine, showing it to be embedded vertically in the ground. |

A cheerful Gareth Brown and Alan Clark prepare the one ton Merlin for lifting from its resting place for the last 65 years. |

As the reader may imagine, putting the garden back as we found it, including rebuilding the rockery took some time – on one of the hottest days of the year! However planning and careful dismantling paid off, plus we came back the following day to finish off tidying up and water all the plants. The engine, once cleaned was mounted on a custom made stand – with the steel being kindly donated by John Robson metals Ltd Goosnargh. We noted that one of the witnesses to the crash, who came forward on the day of the dig, gave a graphic account of an aircraft clearly suffering from some form of mechanical problem. However, the engine shows no apparent evidence of this – it’s like brand new! – in fact, it had only done some nine hours! The valve gear is all intact and shows no signs of failure, ruling out a dropped valve, which would fit with his description. Another possibility would be an ignition problem, but much of the harness was ripped away as the engine buried itself - so no smoking gun there. The engine does appear to have been running at impact, though perhaps not at anywhere near full power, with gouge marks from the reduction gear breaking free being present, as well as a big end bearing having sheared off as it came to a sudden halt and rotational gouges and evidence of bearing failure to the supercharger gearing - all point to it having been turning and stopping very suddenly!

|

|

| The engine airborne once again - albeit briefly, which proved to be the conclusion of the dig as the propeller boss, which we hoped lay below, was nowhere to be found and is believed to have sheared off on impact. |

The rockery reinstated after the completion of the excavation, though we still had much work sweeping the lawn to ensure no metal fragments or stones remained to get caught in a lawn mower's blades! |

Although several instruments were found, they were all in pieces and certainly no possibility of any readings – The same with the throttle quadrant, which was totally smashed, as were the trim controls. We did find evidence that the canopy was still on the aircraft at impact and as it was noted to be open by witnesses, it must have been slid back rather than jettisoned, so bailing out seems not to have been Fairman’s first instinct? as this would surely have impeded his exit? Sixty-five years after the event, we never expected a definite answer, but in our opinion the pilot was definitely in trouble and knew it – But sadly left it too late, for whatever reason, to abandon his aircraft.

|

|

| Fairman's two younger sisters (plain white and blue stripped tops) were able to attend the excavation and here are showing the present owner of the house photos of their brother. | Cleaning the Packard Merlin engine - a filthy job, but someone had to do it!. |

One of the most rewarding aspects of the dig was to be able to give some form of closure to the Fairman family, who had not known precisely where he had lost his life and were able to attend the excavation and see for themselves the site and the engine recovered - it was an emotional experience for them. It seems the family never believed the reported cause for the crash, particularly after one of Roy's RAF colleagues visited the family shortly after the crash and told them that they could discount the official report, as it was well known [to his colleagues] that he had in fact been forced to bail out of a faulty aircraft.

|

|

| The cleaned engine, now mounted on a custom made stand for display - Note: the black painted finish on the engine is all original. | Rear view of the cleaned engine - much of the damage being due to the rest of the aircraft hitting the back of it during the impact. |

Acknowledgements: Fairman family, Morris

family, Alan Clark, Mark Sheldon, Mark Gaskell, Gareth Brown, Frank

Rhoden, Richard Osgood, Thomas Wright, Bob Horridge, Mr Stringfellow,

English Heritage, AIB Report No. W.2094, Kentish Mercury.

This page Copyright © Nick Wotherspoon 2011